What is NATO’s new 5% defence spending pledge, and how will Canada meet it? – National

Canada joined its NATO allies on Wednesday in agreeing to a new defence spending target of five per cent of GDP — but the details are more complicated.

Members of the alliance will have until 2035 to reach the new spending goal, for one thing. And the five per cent is being split into two categories: “core defence requirements” and broader defence-related infrastructure and industry.

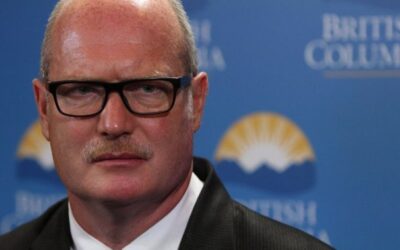

Speaking to reporters at The Hague at the NATO summit, Prime Minister Mark Carney expressed confidence that Canada will achieve its new objectives after lagging behind the alliance’s spending goals for years.

“We’ve arrived at this summit looking forward with a plan to help lead with new investments to build our strength,” he said.

“The investments we’re making in defence and security, broader security, given the new threats that Canada faces — we’re not at a trade-off, we’re not at sacrifices in order to do those. These will be net-additive.”

Carney did note that towards the end of the decade, Canadians would likely need to have conversations around “trade-offs” for continued high defence spending.

David Perry, president of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute who attended the summit in Brussels, said the defence spending increase Canada will have to undertake is the largest since the “massive” ramp-up during the Second World War.

“This is a complete game changer for Canada’s defence,” he told Global News.

Here’s what to know about the new spending pledge and what Canada plans to do in order to achieve it.

What’s in the 5% spending pledge?

The official declaration from the NATO leaders’ summit pledges a new commitment to invest five per cent of GDP annually “on core defence requirements as well as defence-and security-related spending by 2035.”

The pledge marks a substantial increase from the alliance’s previous commitment to spend at least two per cent of GDP on defence, which was agreed to in 2014 and which Canada for years consistently failed to meet.

The new target includes at least 3.5 per cent of GDP on defence expenditures, which NATO defines as funding primarily toward a country’s armed forces. That includes everything from large-scale military equipment like fighter jets and submarines, to ammunition, to salaries and pensions for military members, to related defence forces like national police and coast guards.

The second spending category is up to 1.5 per cent of GDP toward broadly-defined initiatives to “protect our critical infrastructure, defend our networks, ensure our civil preparedness and resilience, unleash innovation, and strengthen our defence industrial base,” according to the summit declaration.

NATO leaders agreed to review the new spending plan in 2029 to ensure it aligns with the global threat environment at that time.

“Our investments will ensure we have the forces, capabilities, resources, infrastructure, warfighting readiness, and resilience needed to deter and defend in line with our three core tasks of deterrence and defence, crisis prevention and management, and cooperative security,” the declaration says.

How will Canada get there?

Canada has long lagged behind the previous two per cent NATO target. According to NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte’s annual report released in April, Canada’s defence spending likely hit 1.45 per cent last year.

Carney previously announced Canada will reach two per cent by the end of the current fiscal year in March — half a decade earlier than previously estimated — with $9.3 billion in new funding.

Much of that money will go toward pay increases for Canadian Armed Forces members and enhancing existing military bases and equipment, while also shoring up the domestic defence industrial base.

Get breaking National news

For news impacting Canada and around the world, sign up for breaking news alerts delivered directly to you when they happen.

“At the core of our defence investment, of course, are the men and women of the Canadian Armed Forces,” Carney said Wednesday while framing the earlier announcement as “working toward” the new 3.5 per cent core defence target.

Carney noted those military members “have not been paid to reflect what we are asking them to do” and have been stuck with outdated or non-working equipment.

“We’re making up for that and level setting that, and that’s an important part of just what we’re doing this year in terms of the increase in defence.”

As for the 1.5 per cent portion, Carney said that will include “ports, airports, infrastructure to support the development and exportation of critical minerals, telecommunications and emergency preparedness systems.”

He added that allies “will buy more equipment and technology made in Canada, by Canadian workers in shipyards, in labs, and shop floors right across our country,” which will not only contribute to that 1.5 per cent portion but also grow the Canadian economy.

“We’ll make the drones, the icebreakers, the aerospace technologies, and much more that’s needed to build a more secure world,” he said.

Carney noted much of the work towards those initiatives is already underway.

He’s previously said the major projects legislation passed by the House of Commons last week — which could become law by Friday after a Senate review — will ensure “nation-building” projects like critical minerals mining and transport will be built quickly.

“Canada has one of the biggest and most varied deposits of critical minerals, and we’re going to develop those” both domestically and with international partners, Carney told CNN in an interview that aired Tuesday.

“Some of the spending for that counts towards that five per cent. In fact, a lot of it will happen towards that five per cent because of infrastructure spending, ports and railroads and other ways to get these minerals. So that’s something that benefits the Canadian economy, but is also part of our new NATO responsibility.”

Carney also noted to both CNN and to reporters Wednesday that as the nature of warfare changes, with threat actors turning to cyberwarfare and pilotless technologies like drones, Canada will pivot toward those priorities as well and costs and expenditures will change accordingly.

That, he said Wednesday, makes it difficult to predict how much Canada will need to spend on defence 10 years from now.

Can Canada achieve all this?

Carney estimated to CNN that five per cent of Canada’s GDP currently equates to $150 billion annually.

Perry said Canada can reach the new spending targets on the timeline set by NATO “if the government actually makes it a priority,” noting it would cost less than what Ottawa spent to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and provide economic supports during that relatively shorter time period.

“That was hundreds of billions of dollars of spending annually,” he said. “This is going to be tens of billions dollars of spending — a huge amount of money, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not nearly as much on an annual basis as we did to combat the pandemic.

“So if the Government Canada wants to see this through, it can absolutely happen.”

Carney said international defence partnerships like the one Canada signed this week with the European Union, as well as the one being negotiated with the United States, will help keep domestic costs down.

“If you all of a sudden start spending a lot more money in one area, you can end up spending a lot more money on rising prices and choke points,” he said.

“That’s part of the reason why we’re co-operating more closely with the Europeans, part of the reason why we continue co-operation with the U.S. in the right areas, but also part of the reason why this increase will happen at a measured pace, or we’ll try to do it at a measured pace.”

Perry noted the wording of the agreement gives Canada and other allies “a lot less rigor and fidelity around the additional 1.5 percent of non-core defence spending.”

Kevin Page, the former parliamentary budget officer and president of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, told Global News the overall spending increase is “feasible, but it will be challenging.”

“We’re going to need to see the strategy and the plan that kind of goes with it,” he said, both in the upcoming budget in the fall and other detailed reports on defence spending.

Where are other allies at?

NATO says it expects all 32 alliance members to reach the earlier two per cent target this year, compared to just three allies in 2014.

According to Rutte’s annual report, only Poland has met or surpassed the new 3.5 per cent target for core defence spending, having hit 4.07 per cent last year.

The United States — whose president Donald Trump has pushed for the five per cent target, as well as Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, spent above three per cent of their GDP on defence in 2024.

The annual report noted that the U.S. last year accounted for 64 per cent of defence expenditures among all NATO allies, with the other 31 members making up the rest.

Rutte on Wednesday credited Trump, who has criticized the alliance and even threatened to not defend members that don’t pay enough for defence, for shifting that dynamic.

“He was totally right that Europe and Canada were not basically providing to NATO what we should provide, and that the U.S. was spending so much more on defence than the Europeans and the Canadians,” he said.

“Now we are correcting that. We are equalizing.”

—With files from Global’s Nathaniel Dove